[As Always, a work in progress. The formatting is a little wonky--particularly the italics, which I use a lot to signify unspoken/inner dialogue and didn't transer over properly. I'll fix that sometime this week. Oh, and as usual, it hasn't been proof-read. ]

Unplanned Pregnancy

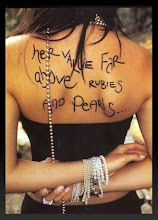

She first noticed it while sitting in a dull coffee shop at the intersection of 106th and 8th, scanning lines of poetry: stressed, unstressed. Stressed, unstressed. Her head felt light, and her temples pulsed, waves of nausea smoothing over her like so many ocean currents. Sonia didn’t think much of it, but later in the week, as her stomach grew increasingly unsettled, rejecting even the tiny morsels she force-fed it, and when her breasts began to swell, large and tender to the touch, she felt a tickle of anxiousness, scratching its spiny finger meticulously down her spine.

By the second week of her missed period, and after three angrily discarded boxes of early-detection urine tests, there was no denying it. Her voice, flat, scarce on the phone one September afternoon, had admitted the two-word truth to her sister: I’m pregnant.

In the past, Sonia’s images of unplanned pregnancies had been categorical, covering every female archetype from prostitutes without the money or sense for condoms, to teenage girls, young and impervious to the insidious dangers of sperm. She even included among her list of examples, the complicated saga of the Immaculate Conception in addition to the typical, if somewhat mundane, drama of the unwise woman whose mother had never warned her, as Sonia’s mother had, that no man would ever buy the cow if he was getting the milk for free. Loose women, naive women, holy women--women with little in common besides an apparently healthy reproductive system and the presence of some mythical creature—a fetus—now swimming within the caverns of their reluctant uteri.

***

Making love had been different than Sonia had imagined—not rosy and pink and sentimental. Instead it was grey, ashy, a curious entity of vigor and pain crossing over her, a numb deep sweeping like a cool wind--there for a moment and gone, quietly. Afterward she did not feel ecstasy. There was no pleasure, but there also was no guilt. It was a moment defined not by what it was, but rather by what it was not.

It was not how her older sister Angelica and her mother explained it to her as a child, during one of many car rides home from eight o’clock mass. It was winter and cold. The heater in their yellow Volvo was slow to warm, heaving and coughing in protest to the frost that had formed and clung to the car. Sonia, then nine years old, shivered as removed her mittens to begin her after-mass ritual, the careful process of imprinting tiny feet on the frosted glass. Her sister spoke slowly, her eyes fixed on the icy road.

At the time, Angelica was nineteen years old and three months newly married, a bride both shy and proud of the secrets she could now share. Sonia’s forehead wrinkled in concentration, aligning the side of her curled fist with the cold glass. A man is only to see you on your wedding night, Sonie-baby—the most beautiful night of a young woman’s life. The little feet covered almost the entire window. He will treat you like a princess wearing white, if you treat him as your King. Sonia added tiny toes with the tips of her pinky. It is a moment of two becoming one. She imagined a baby walking vertically up her window, chubby and freezing and sock-less, and she looked around for something to cover it. A woman must protect her chastity at all times, so that she will not steal from the romance of that moment. The heater had finally warmed, gusts of hot air causing all the feet to slowly disappear, like the ghosts of tiny children fading away, absorbed into the glass before she could warm them.

After the first time they made love, Jamie had disappeared into the other room, appearing to roll off Sonia as one climbs lazily an out of bed in the morning, having been engaged in a dream too dim and faded and unimportant to recall in light of the pending day. The phone rang, its trill ring cutting through the hazy, after-sex silence. Sonia was relieved. She had anticipated that Jamie would be crass after he slept with her, as she often felt he was. But, even his nonchalance toward the mysteries of sex would be better than the alternative. The last thing Sonia wanted after losing her virginity at the age of 26 was conversation—the obligatory, postcoital chitchat, truncated with contrite kisses and thank you’s or, worse yet, whispered utterances of love, hollow phrases describing this moment of loss, this moment of gain. They had just met, and this was not a sacred moment. Just another morning--another lazy getting out of bed. Sonia didn’t love him. And with this, she felt ok.

***

Jamie had been gone three weeks when Sonia discovered she was pregnant. Sonia attempted, despite an always growing sense of uneasiness and fatigue that weighed her down, clung to her like mud—wet, heavy, dark—to act as though there did not exist within her womb a quiet secret that would, sooner of later, blossom into a bloated and odious declaration of one truth or another. Still she found herself staring at her professors in wonder, fast-forwarding four or six months. What will they say? She mused. What would they think of the telltale swelling of belly, the growing mound that would label her, at least in their minds, archetypal woman A, B, or C? ABC.

She pictured one professor, a tall blonde woman with a proud husband and three robust children, gesturing in front of her poetry class. In her mind, the professor resembled a celebrity game show host, with a wide, white-toothed smile and a dramatic voice calling out for her students to strike their buzzers: Come now! Is it A, B, or C? Is she unfortunate, or just plain slutty? You all have a guess, let’s hear it! Buzz, buzz, buzz! A, B, or C, folks—guess correctly and no final exam! Sonia wondered in between fantasies if her belly would be visible beneath her graduation gown in June.

Last summer, Jamie, in a moment of sweetness, had promised to take Sonia on vacation if she graduated in the spring. Four months after that first night together, and she was still with him. When her store manager had offered her an assistant manager’s position at work that would require her to quit school again, Sonia had asked Jamie his opinion. Just finish. Jamie had advised, tender fpr once. You have one more year. You said this is what you want, so finish. Fuck, I’ll pay your rent if you need it. Just finish, baby and we’ll take a vacation in June, ok? To celebrate, ok? Sonia considered the offer and thought to herself, maybe we were wrong about him. Sonia smiled. Somewhere warm? She asked. Somewhere warm.

***

Sonia began to have daydreams about the baby in early December, shortly after the first trimester. On her lunch breaks from her job selling cosmetics at the mall, Sonia would slip over to the children’s section and eye the tiny clothes, petting miniature versions of designer jeans, impractical coats for newborns lined in faux animal pelt. It was during this time, her fingers stroking the soft material, that her mind began to wander.

Would the growing lump in her stomach be a boy or a girl? She concluded that, if it were a boy, she would name him Colin. She was never into sports or cars or anything stereotypically male, but she could learn, if Colin preferred. But she hoped he would be into more intellectual pursuits. Poetry. Not parched, British poets—not Milton or Dryden or Donne, or anyone Sonia felt had been overly canonized. Stressed, unstressed. Stressed, unstressed, she reflected dryly.

Colin would have black hair, like his mother. In her mind suspended a vision of the two of them sitting together in a house, or a straw bungalow on beach, where warm waves pushed thousands of colored pebbles right up to the edge of their grass welcome mat. Together they would sit next to the sea, the sun reclining on the horizon, sand scratching at their bottoms and intruding behind kneecaps, elbows, and Colin, a precocious little eight-year-old, would prop himself up on his sandy elbows and recite lines from poets like Pablo Neruda and Rumi, while Sonia nodded her approval, tapping her pencil to the subtle rhythms, smiling at him, her son.

***

Her sister Angelica’s son was tall and lanky and "hyperactive"—this was the word Angelica had mouthed to guests at her birthday party last year, when little Andy began throw couch cushions across the room, snarling like a lion at his father, who tried to put him to bed early. Jamie had told Sonia he had to work, so she reluctantly put on a scarlet colored cocktail dress and went alone. Before she left, Jamie had given a campy whistle and good-naturedly joked, you’ll have your pick of people to dance with, Sonie- baby, with an ass like that. Sonia rolled her eyes. You come then. We don’t have to stay long. Jaime ran his hand along her cheek. I can’t. You know that. I have to work late. Plus, I can’t imagine your sister will miss me. Sonia responded, teasing. Working late, huh? That’s a very cliché excuse for going to meet your mistress. Jamie wrapped his arms around her waist and smiled at her. You’re beautiful.

***

At the party, Angelica found a few moments away from her duties as hostess to inquire about Jamie. “He couldn’t make it, huh?” Around them, the party was lively, glasses of gin clinking and music blaring from rental speakers. “He had a deadline. Or something. It’s not a big deal to me. We both don’t like parties.” Angelica clicked her tongue as she gestured to a server to grab more ice. “You know, Sonia, relationships are compromise. It’s not all candy and roses and sex. Jacob and I have a serious commitment to each other. He hates parties, too and here he is.” Angelica nodded toward her husband and called out, “I love you, baby!” Jacob waved from the corner across the room where he was nursing a bourbon. “Really, Sonia. I don’t know what you expect, what with you two shacking up and all. I thought we agreed the other day. You just barely met. It’s not a real commitment, just playing house.” Angelica charged on, her eyebrows high, almost meeting the dark, graying crown of her hair. “You know, Jacob and I waited until we got married. And it’s worth it. We have a serious commitment. God created a man to join his wife and become one. When you start deviating, that’s when the problems start. You’ll see—this isn’t you. Trust me, Sonia, you’ll grow out of this relationship—and not a minute too soon. Like I said yesterday, go the church and see Father Andrew. He’ll help you get your head on straight. I can’t even mention how many times he has helped me out of a jam--Oh shit, honey! Not there!” Angelica rushed over to Jacob, who was in the middle of instructing a server to put the ice on the table. “Counter, Jacob. I said ice on the counter.”

***

Sonia had seen the priest earlier in the week. An older man and a friend of her mother’s for many years, Sonia trusted him with her secret. I’m in love. The words sounded awkward and trite, like she had made them up and was trying them out for the first time. Father Andrew smiled and nodded, his eyes amused. I see. And how long have you been in love? Sonia shifted in her seat, her eyes scanning rows of books with titles in Latin she vaguely recognized. About a month? Not long. I don’t really know, Father. All I know is, my sister won’t be thrilled. He’s…not exactly Catholic. Sonia’s stomach twisted. Why the hell does it matter? The elderly man folded his hands and laid them on his chest, thinking for a moment before answering. Well, I have found that the mysteries of love are like the mysteries of grace. He gestured toward the shelves and shook his head. All these books and still no one can fully understand. Some things, unfortunately, can only be understood in retrospect.

***

Sonia continued to daydream about the child. She was helping a woman and her pretty daughter pick a shade of lipstick. The mother gushed, “Oh, her dress is just stunning,” dabbing the corners of her lips with a manicured fingernail. “Sex-ey. The boys won’t know what hit them. The mother and the daughter exchanged a look and laughed, long and loud, at the notion.

If she had a girl, Sonia speculated, things would be different than with Colin. She knew more about girls. They were charming, certainly, but mischievous, as Sonia and her sister had been growing up—sly, like the girl buying lipstick. The girl tapped her foot impatiently. Sonia forced a smile and began to ring up their purchases. “Cash or credit?” The girl shrugged and looked at her mother, who pulled out a large wallet.

Sonia couldn’t blame the woman—if she had a daughter, she too would indulge. Her daughter’s name would be Nonie, and Sonia would buy her pretty dresses, things in pink that she believed all girls--even in a post-feminist movement world--should own. As an infant, the child would be soft, rosy as a cherub. But as Nonie grew, her limbs would stretch, long and willowy like tree branches, stretching out and reaching toward better things--regal and determined and inviting.

***

Angelica gave her a worried look when she learned of the daydreams. “Sonia, I feel like this is too much for you. Please. You know how I feel about it, but for god’s sake, just go to the clinic and get this taken care of. Trust me. In five years, when you are over all this, and ready to have a child, you’ll be glad you did. You’ll be glad you moved on.” So Sonia tried. In fact, she went several times, sometimes with her sister, sometimes without. But each time Sonia attempted to cross the threshold of the clinic door, she would feel a gentle tug on her sweater, and Colin or Nonie would be there asking her with rounded eyes, where they were going. And each time, Angelica would furrow her brow, the creases in her face growing more pronounced. After the third time they tried to go together, and the third time Sonia told her about the children’s large, wondering eyes, Angelica, angry, threw up her palms in frustration and stalked back to the car without a word. Sonia never went back to the clinic, and her sister, to her relief, never mentioned going again. But when Sonia reached the car, Angelica had taken her hand and said again, “You’ve got to move on, Sonia. Move on.”

***

In another English class, Sonia’s white-haired professor waved his hand in front of her and asked kindly if she was ok. He looks like Father Andrew. Father. Father. Sonia looked around the room. All of the girls in her class were engaged, it seemed, blaring testimonials of their relational status settled conspicuously on their fingers. A pretty redhead sitting across from Sonia fiddled with hers, a stone as large as her eyeballs. Promised. Taken. Wanted. Sonia felt sickness sweep over her stomach.

Sonia and Jamie announced their engagement during Friday dinner at Angelica’s house. When Angelica and Sonia were kids, before their father left for the Friday night graveyard shift working security at the hospital, their mother cooked spaghetti. Always spaghetti. They would eat together in front of the television, hurriedly, their mother poised with a bowl of noodles for seconds, their father standing in his brown uniform, and the two sisters in soft nightgowns, greasy tomato sauce glistening down all their chins. Years later, when their mother grew too ill to cook, she asked Angelica kept up the tradition, and Angelica started serving fried chicken—she had always hated spaghetti.

That Friday, when Angelica learned of Jamie’s proposal and Sonia’s acceptance, she slammed the pan of chicken on the table and narrowed her eyes. Sonia looked at Jaime from across Angelica’s dinner table and toyed with her ring. It’s beautiful, she mouthed to him. Sensing tension, Jamie tried to lighten the mood, and offered Angelica a sheepish grin, turning up his palms and shrugging. When little Andy saw this, he too raised his palms to his mother, making a pop-pop noise with his lips each time he lifted his hands. Pop-pop-raise, pop-pop raise. Angelica ignored him and instead turned to Sonia.

Squeezing Sonia’s shoulders between her hands, Angelica shook her emphatically, as though attempting to wake her from a deep sleep. “What is wrong with you, Sonia? God, I just thought this was a fling. Don’t you see this can never work? What would mom say?” Congratulations? Thought Sonia. Jamie cleared his throat, attempting to speak, but Angelica glared at him and proceeded, her words punctuated, methodical, angry. “Oh my god, open your eyes, Sonia.” They are open. Sonia took in the hurt expression on Jamie’s face and wanted to scream. In fact, she wanted to rake her nails across her sister’s face, push her on the ground as she had done as a child, and pull hard at her cheeks. She would tug and stretch until they were so transparent that Sonia could see the skull beneath her sister’s skin, view the bones that would remain long after she died. She would pull until the flesh finally ripped, until she could shake the pinkish wads of skin in front of her sister’s eyes and make her see. He is a human being and I love him. He is flesh and I love him. She would cry this plea until her sister’s eyes filled with tears and she understood that love was not as simple as she had once claimed—that love could not be summed up during the course of a car ride. 123, 123—just follow the steps to perfect romance! ABC, ABC, which woman am I now, Angie, A,B, or C?

But Sonia, as always, said nothing. Angelica finished by closing her eyes, emphasizing with her body language the importance of what she had to say. “I love you. You know I love you. Please. Don’t do this. Don’t be stupid.” Angelica opened her eyes, bringing her face close to Sonia’s, and said, this time softly, in a whisper, “Please. Just think about it. Think about what Mama would say. Please.”

***

What would Mama say? Sonia wasn’t sure anymore. She was protective of her girls--that was certain. When Angelica was a teenager, she was required to take Sonia along whenever she went out with boys. These were good times, Sonia recalled. After school, they would play baseball, or go fishing, Sonia and the boy standing with poles poised at the edge of the river, dipping their feet into the dark cool, while Angelica sat moodily in the background picking her fingernails, waiting. After an hour or so, Angelica would announce it was time to go, and Sonia would sit in the backseat of their mother’s car behind the boyfriend. Wait here, Angelica would call back to Sonia as she parked in front of the boyfriend’s house. I have to get something. Sonia watched her sister and the boy disappear into the unfamiliar doorway and waited. Every time this happened, Sonia contemplated leaving and telling her mother, but in the end, curiosity always won out, and she would strain her eyes, attempting to see past the curious curtained windows and into her sister’s life. Her legs were sweaty, sticky against the plastic seat, so sometimes Sonia would sit on the curb, poking at the grass with a stick. The soil beneath the grass was dark and cool and tempting. When she was sure no one was watching, Sonia thrust her stick into it, pushing the stick in further each time, pulling out more and more dirt until the grass was spotted with a series of holes, deep black caverns replacing the green. When she was finished, Sonia quickly filled the holes with leaves and uprooted grass, smoothing the places she had dug to conceal them from her sister’s prodding eyes.

Whenever she returned, Angelica refused to explain herself, but merely started the car, allowing her sister to wonder why her hair was mysteriously tousled, her blouse slightly askew. Instead of speaking, she only winked and smiled a secret smile, leaving Sonia always with more questions than answers. She never asked about Sonia’s dirty knees.

***

Sonia still drove the old Volvo. Her mother had left it to her before she died of a brain tumor two years earlier. Sonia had refused to get rid of it, though the once-bright yellow had dulled from years snow and rain. Even before her mother had been diagnosed, as a child, Sonia always thought she would rather die of cancer than a car accident. Television programs told her of brave young cancer patients, whose time to reflect on the intimate bond of life and death had allowed them to leave their loved ones with words of candid wisdom. Sonia pictured how she would say goodbye to friends and family, her balding head wrapped sweetly in a linen scarf. She thought about how her legacy of strength in the face of terminal illness would undoubtedly trump, for both her mother and for God, the many times she had fought with her older sister. Slowly. Carefully. With time to reflect, to let go. This had been how it was with her mother: heartbreaking, yes--but not surprising.

Accidents, however, were sudden. Bleak. Permanent. Sonia hated to think about it. One night after work, in the comfort of their bed, Jaime had told her about a student he knew who died at the age of twenty-three. The young man, he explained, had been fixing his bathroom sink, his head lodged inside the cupboard while he twisted his wrench back and forth. Seconds later, the sink, an artifact of antiquated, heavy porcelain, somehow disrupted from its place, had fallen on the boy, crushing his head beneath its ancient weight. His life had ended there, with swift, horrifying finality.

To Jamie, the story was ironic, amusing. He stopped talking and patted Sonia’s back, rolling over and falling asleep immediately. Sonia was sickened. In the darkness, her eyes stared at the emptiness of the ceiling, and she thought of the boy, his brains slipping and sliding down pipes and rotted wood. Some mysteries better understood in retrospect.

Sonia thought of this phrase during the funeral. It was smaller than the service for her mother, who was a devout member of the church. Jaime hadn’t had much family, but the few who attended the service threw bitter glances at Sonia as pressed wadded up tissue to their faces. The scene from the week before haunted Sonia, a fragmented reel of broken-up pictures on repeat in her mind. Nothing seemed real. Ignore them, her sister had said, seeing her face grow pale. You loved him. She embraced Sonia. You can’t change the past. Just let it go. Sonia’s stomach tightened and nausea overcame her. Father Andrew had not finished the funeral rites before she ran, stumbling, to the bathroom and vomited.

***

Sonia had never been good at driving in the rain and didn’t protest much when Jamie insisted on driving, even after four glasses of Bookers Fine bourbon. He did it all the time, after all. The yellow Volvo skidded onto the side of the old freeway, uprooting weeds and grass until it slammed into a telephone pole, jolting from the impact. As the tires settled into the mud, the car whined and sputtered until the engine died completely, and the only sounds to be heard for miles were not voices or cars, but droplets of water tap-tap tapping lightly against the roof like the harness syllables of some long, sad poem, stressed, unstressed, stressed, unstressed.

After some time, when she came to, blood pounded in her head, and her hands were unsteady. She took a deep breath. Alive. Shaking, but alive. We’re alive, baby. Rapturous, Sonia looked at Jaime, her heart swollen with the joy of it all, ready to embrace, to breathe a sigh of relief and laugh that they had finally outlived that goddamned Volvo, laugh that after all the bullshit, they were still together. But Jamie, for once, was quiet.

Sonia turned toward him. Touching his face, her body quivered, the energy of joy converted to trembling. A grunt escaped her throat. Blood dribbled down Jaime’s stubborn chin from the place where his head had collided with the windshield. Sonia wiped some off and rubbed it gently between her fingertips. Dark. And sticky. Jamie’s face was slumped over the dashboard, arms curled up next to his body, as though trying to protect himself. To Sonia, he looked like a fetus, an a stillborn child wedged affectionately within a mother’s warm womb, floating trancelike next to internal organs, alive but not alive. A child absorbed into nothingness, into the glass, into amniotic fluid, before ever fully entering the realm of life, like some rich, ethereal dream.

***

The doctor, a handsome man, brought Jamie’s baby wrapped in the fuzzy yellow blanket Sonia had bought on one of her many trips to the children’s section. In the background, Angelica argued with a nurse about the size of the room, her husband, Jacob, attempting to soothe her while amiably raising his cup of coffee to Sonia in congratulations. Around her, life proceeded as usual. Sonia looked at her child.

The baby was small and wrinkled, like a peanut or a grandfather, with sparse bits of hair spotting the head. Its face was angry. Angry to be alive? Sonia wondered. The baby’s features collapsed into a rhythmic cry, and before Sonia laughed at baby’s indignant wailing, her eyes dampened. You are real, she thought. I have brought you here. Sonia held the child to her breast and wept.

Wednesday, February 11, 2009

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)